Gaps in ambition, implementation cloud the way forward in meeting climate-change goals, says DBS Group Research

Since the wide-scale use of fossil fuels enabled the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s, this energy system – where oil, gas and coal are burned – has gradually evolved to become the lifeblood of the modern economy.

While a fossil fuel-driven modernisation has vastly improved the lives of millions of people around the world for the past 200 years, its ongoing use has caused lasting harm to the climate.

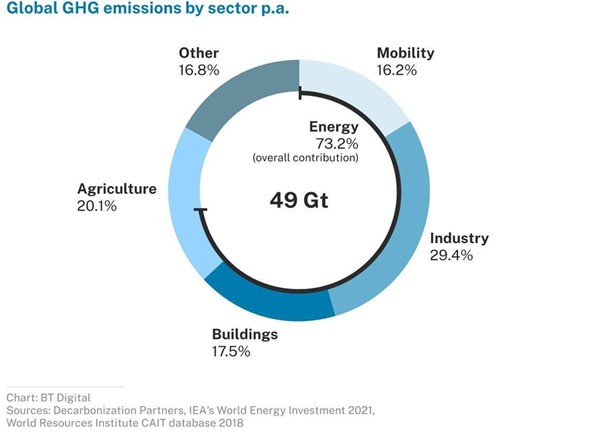

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), humans have used 2,475 gigatonnes (Gt) of emissions since the 1750s. That leaves only about 500 Gt of carbon budget, or about 10 years’ worth at current rates, to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5 deg C.

While the world saw its first big energy transition when it shifted from the burning of wood and charcoal to coal for the purposes of industry, there is an urgency for the next big energy transition from fossil fuels to cleaner forms of energy.

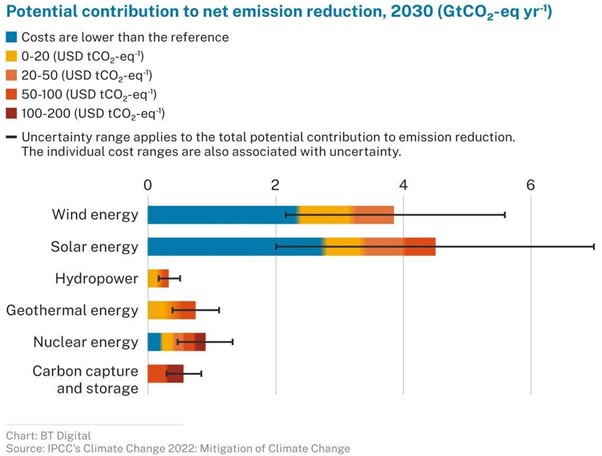

Thus far, energy transition has been dominated by renewable sources of energy – chiefly, solar and wind. The technology and markets for these have matured, and the costs of implementing them has gone down over the years.

Yet, there has not been enough implementation of these relatively achievable and accessible forms, and a heavy reliance on fossil fuels remains.

Observers say the main challenge has been the lack of political will to accelerate the energy transition.

Unlike the Covid-19 pandemic, which was treated as a global emergency that needed to be addressed with urgency, Subodh Mhaisalkar, an engineering professor at Nanyang Technological University and the executive director of its Energy Research Institute, said that climate change has not yet become the “burning platform” that demands urgent action.

“Technologies and policy tools to address the low-hanging fruits (of solar and wind energy) are available; a collective will for action is yet to be visible,” he added.

While almost 200 countries are party to the Glasgow Climate Pact, which was the outcome of the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), DBS Group Research analyst Suvro Sarkar noted that there is an ambition gap as well as an implementation gap that is clouding the way forward in meeting climate-change goals.

“Policy changes are required to create a sustainable ecosystem with the right incentives, in order to accelerate the move towards cleaner energy sources,” he said.

Given that energy transition typically cuts across various sectors, Gilles Pascual, power and utilities leader for Asean at professional services firm EY, said that comprehensive road maps and an overarching requirement to green the financial system to redirect capital flows are needed.

“While there can be apprehension from governments to act quickly before getting the full picture of a sector-wide strategy, short-term measures and action can turn low-hanging fruits into reality,” he added.

Decarbonisation solutions available in the market

Solar energy is undoubtedly the most affordable source of renewable energy. The business model is well-established, the solution can be deployed quickly, and there is a lot of capital available, said Pascual.

Using data from IEA, global asset manager BlackRock said that solar costs have declined by 85 per cent since 2010.

The Asia-Pacific region is already the global powerhouse for renewable energy, representing over 50 per cent of installed capacity and more based on forecasts, based on figures from investment data company Preqin.

Besides investing in energy infrastructure, Pascual pointed out that one often-overlooked method to reduce carbon emissions is simply to improve energy efficiency.

This includes switching to light-emitting diodes in residential and commercial buildings, deploying energy efficient air-conditioners and chillers, as well as using district-cooling technologies, said Mhaisalkar.

New opportunities

Beyond the tried and tested, new avenues for energy transition, such as carbon capture, electric-vehicle (EV) charging, battery storage and offshore wind, are emerging.

These solutions have been taking advantage of falling costs, rising scale economies and improving commercial viability, said BlackRock Alternatives.

Some examples of new clean energy sources that have managed to scale include lithium-ion batteries and smart grids in the energy sector, point-source carbon capture and using alternative materials for the building sector, as well as EVs in the transport sector, said Decarbonization Partners, a joint venture between BlackRock and state investment firm Temasek that invests in decarbonisation solutions.

Sarkar believes that hydrogen would be a crucial element for countries to achieve their net-zero emissions target, and more are developing hydrogen plans.

While Europe remains the centre of hydrogen development, Asia-Pacific markets have also started venturing into this space, with South Korea and Japan being the first movers in this region.

China expects hydrogen to comprise 10 per cent of its energy share by 2050 to reach its ambitious climate targets. Indian private-sector companies are investing in electrolyser and fuel cell gigafactories, aided by production-linked incentive schemes, he added.

As for Singapore, the city-state does not have adequate infrastructure or land to accommodate large-scale facilities for the mass production of renewable energy-powered green hydrogen, although the Energy Market Authority has recognised the use of hydrogen as among the best solutions to meet emission targets.

However, Sarkar said that Singapore can import green hydrogen and also emerge as a trading centre as well as research and development hub in the region for research in low-carbon solutions, including green hydrogen.

While also noting the potential of hydrogen, Mhaisalkar said that cost reduction and scaling are the major challenges that should be addressed over the next decade.

There is currently no mass production or deployment of these newer technologies, said Sarkar.

“Costs of new technologies such as green hydrogen will probably need to reduce 50-80 per cent from current levels over the next decade or so, in order to meet critical mass criteria,” he added.

“This may seem a stiff target, but given the experience the world has had with renewable energy sources – where costs have fallen much faster than expected – it is not an improbable one.”

From an investment point of view, Sarkar said that pure play companies in emerging technologies are likely a better bet for private investors than public markets.

“Hydrogen fuel cell and electrolyser plays are still very much in the startup phase and will likely not be profitable on the bottom line yet; hence investors will need to fall back on price-to-sales ratio as one of the key valuation metrics,” he said.

Mixing the not-so-new with the new

It is important to note that these emerging sources of clean energy, such as green hydrogen, are not competitors to renewables, said Sarkar.

“Rather, it is complementary and synergistic to the growth of wind and solar in future,” he said.

As government and supranational bodies such as the European Union impose regulations to tighten carbon emissions even more in the future, carbon compliance prices will rise even higher.

Cost inflation for carbon-intensive industries will likely prod them to ramp up investments in wind, solar, as well as emerging sources of clean energy, such as hydrogen, said Sarkar.

He estimates that existing technologies will contribute to 80 per cent of curbing carbon emissions over the next decade, while new technologies will account for the rest.

Given that some renewables such as wind and solar are already mature businesses, governments can focus on enhancing the electric grids to handle higher loads, with expected growth in electrification in future, and also ensure grid connectivity to areas which generate renewable energy rather than fossil fuel-based sources.

Investments into grid-level battery energy storage systems will improve grid flexibility and its ability to handle higher loads, which makes renewable energy systems such as wind and solar more available and reliable, given their intermittency.

“The key pathway to decarbonisation is the electrification of energy use,” said Sarkar.

“Countries will need to ensure a higher proportion of cleaner energy sources in the power sector, while simultaneously promoting the electrification of end-user segments, such as transport and buildings.”

A system overhaul

Despite all the technologies available today, Mhaisalkar said that close to 50 per cent of the world’s energy needs will still rely on fossil fuels by 2050.

“We will exceed the 1.5 deg C temperature rise milestone by the end of this decade, and a 2 deg C temperature rise before 2050 is forecasted,” he added.

Observers say there needs to be an overhaul of the current economic system, in addition to negative carbon technologies.

Mhaisalkar said that policy changes, such as removing all subsidies on fuels and higher taxes for larger users of electricity, are important first steps.

He also suggested instituting legislations on the installing of renewables on rooftops and other measures to increase decarbonisation for industry.

“After decades of a ‘growth at all costs’ mentality, the formidable task of reversing a millennia-old positive correlation between gross domestic product growth and carbon emissions requires no less than a thorough overhaul of our economic modus operandi, attainable only through disruptive new technologies – which include innovations in green energy,” said Hou Wey Fook, chief investment officer at DBS.