Foreign Exchange Risk Management

Foreign exchange risk is the most common form of market price risk managed by treasurers – the other common ones being interest rate and commodity risk. Market price risk is one of several groups of risks that businesses must manage within their ERM (Enterprise Risk Management) framework. See the Risk Management Treasury Concept for more on ERM.

Introduction

Like all risks, Foreign Exchange (FX) risk is managed using the standard risk management process, which looks something like this for FX:

| Identify: |

| Gather underlying exposures from cash flow forecasts |

| Analyse: |

| Determine Value At Risk or other metrics of FX exposures |

| Treat: |

| Hedge with forwards (or options and combined strategies) |

| Monitor: |

| Daily mark-to-market to ensure that hedging works as intended and risk limits are not exceeded |

Generally, most treasury effort goes into determining the underlying exposures, and then analyzing them. This is because uncertainty within most commercial businesses, combined with often ill-suited reporting systems, makes it difficult to be sure that FX exposure forecasts are accurate.

Objectives of FX risk management

Before looking at exposure determination, businesses must decide what are their objectives for managing FX risk. This includes:

What to hedge?: Some businesses only hedge what is on balance sheet (i.e. cash, bank balances, accounts receivable and accounts payable), while others hedge orders and forecasts to the extent that they are exposed to FX losses from pricelists and / or contractual obligations. On the other hand, some businesses do not hedge at all, believing that over time FX rates will revert to mean, and gains in one decade will offset losses in another decade. However, this is not tenable for most businesses who’s whose shareholders expect consistent results since it may generate material cashflow volatility.

Why hedge?: ultimately, hedging aims to ensure consistent results and to reduce FX volatility between forecasts and actual performance. This begs the question of what performance metric is given priority – some businesses hedge to manage accounting results and other businesses hedge to manage cashflow or economic performance.

How to hedge?: businesses must decide on how to treat FX risk. The most common hedge for FX risk is forward contracts but other alternatives (or complements) include FX options and natural hedging.

The cashflow vs accounting dimension, in particular, has material impact on the actual hedging process and decision making.

FX exposures are normally categorised into three types:

Transaction exposures: these come from selling and buying activities using different currencies, balances in different currencies and FX financial transactions like foreign currency loans and deposits.

Net investment exposures: these come from owning subsidiaries in foreign currency. When their value is consolidated, there will be exchange differences in the accounts. From a cashflow perspective, a foreign subsidiary can be considered as a FX asset (either for its net asset value or for the dividend income derived from it).

Economic or strategic exposures: these come from the business’ competitive landscape, for example, having a competitor operating in a different base currency may make FX rate changes into a strategic competitive risk.

Hedging for each of these FX exposures will require different forecasts to determine the exposure and different hedging tenors and methodologies to manage the FX risks.

FX risk management policy

The above must be expressed and specified in a clear FX policy which is typically written by treasury and approved at the board level. The FX policy must clearly articulate the following details:

Hedging objective

What is to be hedged

Hedging tenor

Hedging methodology

Instruments to be used

Delegations and controls

Risk limits

Like all policy documents, the FX policy should have an annual drop-dead clause to ensure that it is reviewed and approved by the board annually to cater for changes in markets and situations.

Unknowable future

Managers and even treasurers are sometimes inclined to believe that they can predict FX rate movements. Some of the smartest firms on the planet spend hundreds of millions of dollars to hire in-house economists and leverage technology such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) etc. to try to predict FX rates, and no one succeeds over time.

Treasurers must accept that, even if certain developing currencies may look like a one way bet for significant time periods, the future is unknowable. This why treasurers need to follow a clear FX policy that spells out how they must hedge the business’ FX risk.

Identifying FX exposures

Once the policy has been set, which is normally an infrequent activity, treasuries need to identify the FX exposures that must be hedged. This is the most critical part of FX risk management – inaccurate exposure data will lead to wrong hedging which will increase, rather than reduce, volatility.

FX exposures are derived from FX cash flow forecasts. Cash flow forecasting is the foundational requirement for all treasury operations – treasury cannot be managed effectively and safely without cash flow forecasts. Most treasuries will need different cash flow forecasts such as:

Cash positioning: 3 – 30 days forecast of flows in and out of each bank account, used to manage day-to-day bank balances.

12 month cash flow: a rolling 12 months base currency forecast of cash flow by subsidiary or business, used to manage subsidiary funding needs and liquidity, and group level funding

3 – 7 year strategic or long term cash flow: rolling long term group level cash flow forecast, used to plan long term funding and liquidity at the group level.

FX cash flow: FX cash flow forecast, usually rolling 6 – 18 months depending on the business’ exposure tenor, used for hedging FX exposures.

The FX cash flow forecast is typically different from the 12 month cash flow which is normally in base currency. For FX risk management, we need to know the cash flows expected in each currency. In some cases, the 12 month cash flow may be in transaction currency, in which case this can be used for FX risk management as well as for the subsidiary’s and group’s short term funding and liquidity.

Direct and indirect exposures

When forecasting FX cash flows, it is important to identify the economic exposure currency, particularly if it’s different from the invoice currency.

A local currency invoice may hide a currency clause or automatic repricing of a commodity globally priced in USD. This is referred to as indirect FX risk. When the invoice currency is the same as the risk currency, it is referred to as a direct FX risk.

Indirect FX risk can arise when the underlying product or commodity is globally priced, for example in USD, but the invoicing currency is a local currency because local currency is easier and cheaper to settle domestically. Even though the invoice is in the local currency, the amount will vary monthly depending on the global USD price for such products or commodities.

Currency clauses can also distort reported or apparent FX exposures, because they may trigger changes in the invoice currency amount depending on the market price of the other currency stated in the currency clause. For this reason, currency clauses should generally be avoided, and if they cannot be avoided currency clauses must be notified to and preferably approved by treasury.

Analysing FX risk

FX risk, both before and after treatment or hedging (also known as gross and net exposures), is commonly analysed in the following ways:

Notional exposure: This refers to the notional amount of the currency exposure defined as forecast currency inflows less currency outflows. Gross notional exposure excludes hedge transactions whereas net notional exposure includes hedge transactions. These are often translated into base or functional currency for ease of reading, but given that these are FX exposures, the choice of FX rates for such translation may have a big impact on the perceived exposure.

Mark-to-market: The notional currency exposure is translated at the relevant forward rates for the cash flow dates to determine their current market value in base currency. This can be done for gross and / or net exposures; and this is often compared with the mark-to-market at the time the exposures were fixed, created, or known, to produce the mark-to-market profit or loss (also known as unrealized gains or losses).

Value at risk (VaR): This refers to the value across the portfolio of FX exposures by applying the historical volatility and correlations between currencies, and it represents the maximum loss of the FX exposure portfolio within a certain unwinding period (typically 24 hours or one week) and with a certain statistical probability (typically 99% but sometimes 95%).

Stress testing: As VaR typically only uses 12 months of FX rates (and extreme FX rate movements often occur at longer intervals than one year), it is good practice to stress-test the FX exposure portfolio (sometimes gross and always net) against worst-case rates; these can be the worst rates observed over decades or arbitrary extreme rate changes such as 10% for OEDC and 20% for others (or larger percentages at management’s discretion).

Such analysis will form the basis for FX risk management evaluation and must be specified precisely in the FX policy.

Hedging FX exposures

Treating FX risk is normally achieved with some form of hedging. Commercial (non-financial) businesses typically use some or a mix of the following forms:

Natural hedging: This means buying in the same currency as sales are in. Although this sounds like an easy solution, it is normally not effective because suppliers and customers may price the FX risk result for themselves higher than the business itself. Natural hedging is often inflexible because the required commercial agreements are typically harder to change than buying and selling currencies forward.

Loan hedging: it is possible to hedge currency sales (a future cash inflow) by borrowing in the sales currency (repayment of loan is considered to be a future cash outflow) and to deposit purchase currency for the opposite reason. In practice, access to sufficient credit lines and the large loan to deposit spread makes this an expensive way to hedge. It may make sense where funding is anyway needed and a currency loan can hedge for recurring business. This can also be useful where the forward market is non-existent or severely restricted.

Forward hedging: This refers to selling the exposure currency forward against the base currency for sales and future inflows (and the opposite for purchases and outflows). This is normally the most cost efficient and effective way to hedge FX risk, and is described in more detail below.

Option hedging: This means hedging the FX exposure using FX options. It is not uncommon in commercial businesses to hedge special situations such as bids and tenders where the FX exposure is material but uncertain. For normal FX exposures and assuming no view of FX rate movements (see “Unknowable future” section above), options will always be more expensive than forwards over time because the option buyer pays a premium for flexibility they do not use if they have no market view.

An example of Forward hedging

A business with USD as its base currency concludes a sales contract in EUR to sell a widget for EUR 100. The current spot exchange rate is USD 1.25 = EUR 1.00. The cost of delivering the widget is USD 100. So, at contract date, the business expects a profit of USD 25 (sale EUR 100 = USD 125 less cost USD 100 = profit USD 25).

Without hedging, the business is subject to FX rate volatility – for example, if the EUR rate goes down to 1.00, there will be zero profit. Conversely, if the EUR rate goes to 1.50 the profit will be USD 50.

The business’ gross FX exposure is the future inflow of EUR 100. Since USD is its base currency, all USD flows are, by definition, not FX exposures. The principle of FX hedging is to create an equal and opposite hedge flow to offset the exposure flow using one of the techniques listed above.

In summary, to do a forward hedge, the business will sell EUR 100 forward against USD for maturity on the sales contract due date when the business will receive payment of EUR 100 from their customer. With the forward hedge in place, on the due date, the business receives EUR 100 from customer and pays EUR 100 to the bank (with whom they did the forward) and the bank pays the business approximately USD 125 as the forward rate is a function of the spot rate and the two currencies interest rates (see “Forward pricing” below). Thus, the business has preserved USD 25 as its expected profit margin.

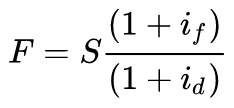

Forward pricing

The forward rate is not a prediction of future spot rates. It is simply the arithmetic application of the two currencies’ interest rates to the spot rate.

The spot rate is the standard current rate which is quoted by market convention for two banking days after the dealing date. For example, trading spot on Tuesday is for settlement on Thursday. Trading for same day or next day settlement is possible; however the rate will be slightly different from the spot rate which is the reference rate shown on market data services. Forward rates are for any date later than spot, and are conventionally quoted for 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months from spot (same tenors as for interest rates).

The reason that the forward rate is simply the spot rate adjusted for the interest differential is that forward cash flows can be constructed using borrow-spot-invest.

Taking the example above, where a USD business is selling a widget for EUR 100, and without forwards, we can implement a hedge (i.e. sell EUR 100 forward against USD) as follows:

Borrow EUR 100 which creates an EUR outflow at maturity

Sell the loan proceeds of EUR 100 spot against USD

Invest the USD 125 from the spot for the same maturity

The initial flows result in zero (EUR borrowing proceeds sold and USD spot proceeds invested) and the maturity flows are the same as a forward would be (EUR outflow to repay EUR borrowing and USD inflow from maturing investment).

This is why the forward rate is equal to the spot rate multiplied by the interest differential (between foreign interest rate and domestic interest rate) discounted to spot date. Arithmetically, this can be expressed as:

This knowledge makes it easy to calculate approximate forward rates and hedging costs in the absence of a market data source, simply by knowing the spot rate and the two interest rates.

Option pricing

While forward contracts are firm commitments to pay the sold currency and receive the bought currency at an agreed future date, options give the buyer of the option the right, but not the obligation to receive the bought currency and pay the sold currency at an agreed future date. The option buyer pays a premium at the spot date for this flexibility.

In general, commercial businesses should not use options to hedge FX risks because:

In the absence of a market view, options will always be more expensive than forwards (because of the premium paid for extra flexibility) and

Commercial businesses should not take market views (because the future is unknowable)

Exceptions (with caveats) can include bid and tender and price list risks where the underlying FX exposure is material but uncertain.

Another reason for commercial businesses to avoid options is that the options market is skewed in favour of options sellers, whereas hedgers are normally options buyers. This is because most humans are risk averse i.e. option buyers, and since the supply of sellers is limited, the market is skewed in favour of sellers – the law of supply and demand in action.

The option premium is priced based on two factors:

- The intrinsic value of the option – simply the arithmetic difference between the option strike rate and the corresponding forward rate:

- “at the money” means the option strike rate is the same as the forward rate (this is the default basis for option pricing);

- “in the money” means the option strike rate is better than the forward rate (resulting in an expensive premium so very rare);

- “out of the money” means that the option strike rate is worse than the forward rate (sometimes used to get a cheaper option premium).

- The time value – the value over time that market volatility will bring the option strike rate into the money and make the option profitable. Therefore, the longer the option, the more expensive it will be.

Time value is also affected by the type of option.

American options can be exercised at any time from spot to maturity and are therefore more expensive because they are more likely to be in the money at some time during the life of the option as the market moves up and down.

European options can only be exercised at the maturity date and are therefore cheaper than American options.

FX options are almost always European type options.

It is the time value that allows market observers to derive the implied volatility from option trading and compare that with the actual (recent historical) volatility.

There are many different option pricing models in use, which creates opportunities for model arbitrage. Fisher Black and Myron Scholes developed the most popular pricing model for equities in 1973. This was adapted for FX options by Garman and Kohlhagen in 1983, and the Garman-Kohlhagen model remains the default for FX options today. Many trading systems and treasury management systems allow the user to choose between Garman-Kohlhagen, Cox-RossRubenstein, and binomial models amongst others.

Monitoring FX risk

After hedging the FX exposures, treasurers continuously monitor the net FX exposures on the basis set out in their FX policy, which will normally include some combination of

Nominal exposure

Mark-to-market

Value at Risk (VaR)

Stress testing

This will normally be automated by the treasury management system and / or trading systems, which will continuously (near real-time) or at least daily recalculate these metrics using current market rates and flag any limit breaches or other exceptions.

Tax on FX hedging

Forwards and other hedging instruments will generate gains and losses, which may or may not synchronise with losses and gains on the underlying FX exposures. When they are not synchronized, this may create tax exposures that can be hard to manage.

One cause of de-synchronised gains and losses may be due to tax authorities requirements on whether financial instrument gains and losses should be recognised for tax purposes on a cash (a.k.a. realised) or a mark-to-market basis.

Generally accepted accounting practice (GAAP) requires period end re-evaluation of FX exposures for accounting and reporting purposes. Not all tax authorities allow taxation to follow accounting practices.

Another source of de-synchronisation can be when hedging is done in a different jurisdiction than the underlying exposure. This can happen when hedging is centralised and not booked back to subsidiaries, and when onshore hedging is not available or too expensive, so hedging is done offshore.

For these reasons, treasurers and the board must ensure the tax team sign off on the business’ FX policy.

The information herein is published by DBS Bank Ltd. (“DBS Bank”) and is for information only.

All case studies provided, and figures and amounts stated, are for illustration purposes only and shall not bind DBS Group. DBS Group does not act as an adviser and assumes no fiduciary responsibility or liability for any consequences, financial or otherwise, arising from any reliance on the information contained herein. In order to build your own independent analysis of any transaction and its consequences, you should consult your own independent financial, accounting, tax, legal or other competent professional advisors as you deem appropriate to ensure that any assessment you make is suitable for you in light of your own financial, accounting, tax, and legal constraints and objectives without relying in any way on DBS Group or any position which DBS Group might have expressed herein.

The information is not directed to, or intended for distribution to or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of or located in any locality, state, country or other jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation.

DBS Bank Ltd. All rights reserved. All services are subject to applicable laws and regulations and service terms. Not all products and services are available in all geographic areas. Eligibility for particular products and services is subject to final determination by DBS Bank Ltd and/or its affiliates/subsidiaries.